How to Draw a Volute in Autocad

Design before you build

I worked in finish carpentry and millwork for quite a while before I learned that you have to design things before you can build them: the less confidence I had about each step of a job, the more important it was to plan right to the end, before cutting one piece of wood.

(Note: Click any image to see a larger version. Hit "back" button to return to article.)

Some time later, I figured out that I didn't have to design everything from scratch — lots of smarter carpenters had built most of the same stuff before. What I really had to do was look at their work! From that experience, I've learned that the correct way to build a house is to design the handrail first, then design the stair, and the rest of the house will follow.

I'm not at all self-taught. I went to school for woodworking, and I was lucky to have a superb teacher. And I was lucky to work for and with some really good, experienced, and generous carpenters on job sites, and woodworkers in mill shops. In fact, A 75-year-old master named John Mesiti taught me woodturning, which got me into stair building.

But I couldn't find a living stairbuilder to teach me everything I needed to know about the trade, so I had to learn from dead ones: craftsman who left their techniques behind in books; carpenters who left their work behind in old homes.

While learning to build stairs, one of the biggest problems I encountered was how to make a volute. What is a volute?

Pronounced Vol-ute, depending on where you hail from, the word originates from natural forms, like unfurling leaves, the shells of mollusks, or gastropods and ram's horns.

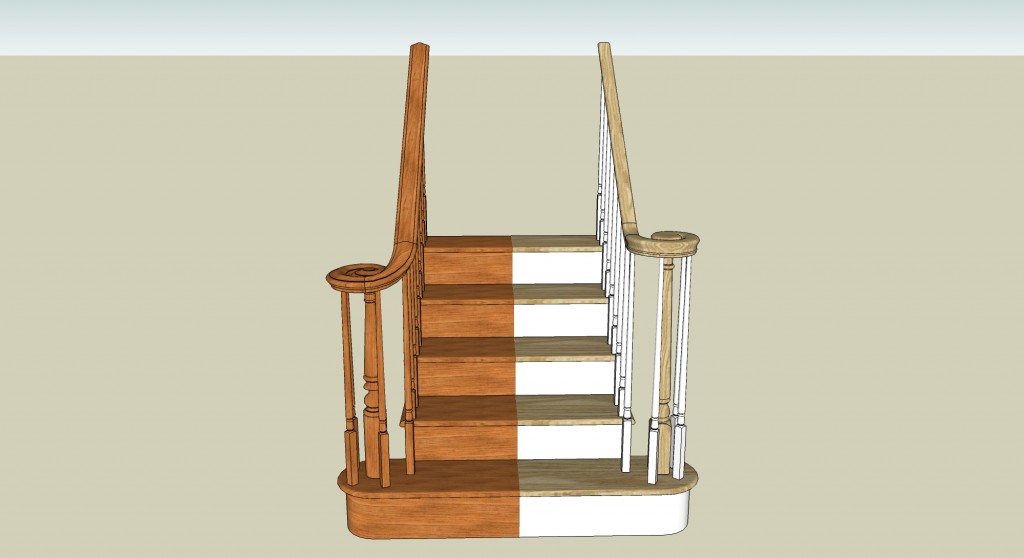

Come on! A volute is one of the most beautiful pieces of wood in a home. It's the curved piece on the bottom of the stair; it's the spiral, the beginning on the way up and end on the way down of every proper stair; a volute is the piece that supports the birdcage of balusters at the starter step.

The spiral volute design appears on fiddleheads both of the fern and the violin, and pairs of volutes decorate the capitals of the Ionic order. Volutes play a role in the old mystic golden number — the Fibonacci series, they have a kind of magic.

In fact, if the house is a body, and the handrail is the main artery, then the volute is the heart of a home.

And for carpenters, volutes provide a natural termination for linear molding and handrails.

For hundreds of years volutes have been a favorite way to start a stair rail, first because they are pleasing to the eye and, second, because they are comfortable to the hand. They lend a gentle slope to the start of every stair. Viewed from above, a volute spirals down into an eye, a focus, like the place where you drown in a whirlpool, where everything begins and ends — nothingness.

But I'm going off on a tangent, as usual, and Gary's going to get upset with me. Back to carpentry.

Commercial volutes

Even commercial handrail systems — available from local lumberyards — include volutes. They are always the most expensive parts in the catalogue. High-end stair part companies offer handsome volutes and attractive stairs can be built with them. But for the most part, manufactured volutes have a few failings:

- They aren't available in a wide range of species

- They aren't available in a wide range of patterns.

- Available patterns are not for the most part historically correct.

Machine-made volutes are primarily designed for just that — to be made on automatic or semi-automatic machinery. The curves are kept open so that rotating cutters can reach into every curve, which means the rail never spirals in on a center — they have no eye…exactly, they have no vision, they fail to provide a natural and necessary visual termination and starting place for railing.

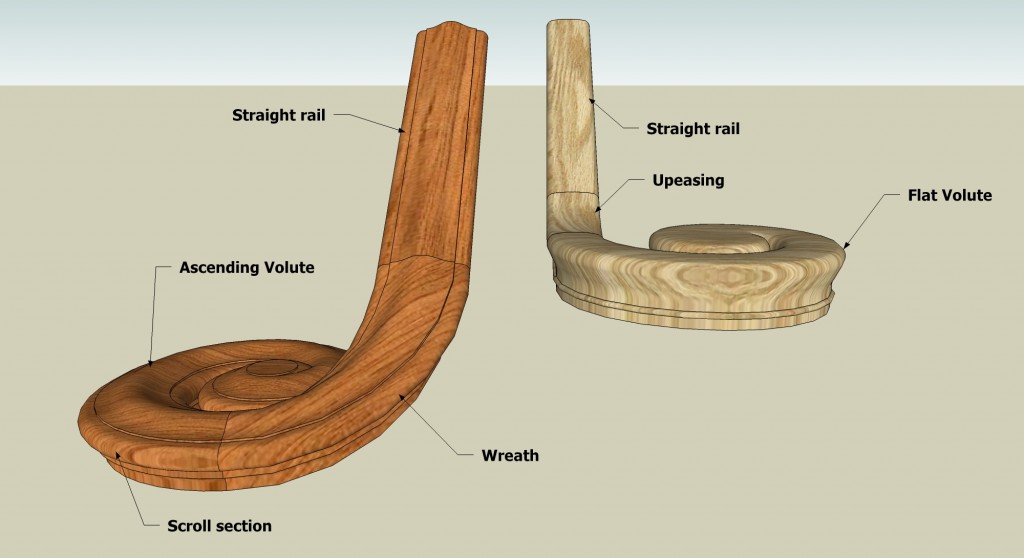

A commercial volute with an 'upeasing' (right) must be installed higher above the starting step than a volute with a wreath (left).

In addition, for ease of construction, commercial volutes curve in elevation, and then curve in plan — they have no compound curves, which means they remain level until the second tread and must be set high on every stair. For that reason, commercial volutes require long balusters and tall newels; a person starting up such a stair must raise their hand uncomfortably high. (See Fig. 5)

Fig. 5

~~~

Why carve a volute?

When I started building stairs, all manufactured parts were made of beech, and all the old stairs I looked at were mahogany or walnut. I had to make rail. And I had to make complex curved parts. The volute seemed like the hardest part to make. But it doesn't have to be — not if you start with a good drawing. In fact, a full-size drawing makes the best template, too.

If you want to build the best stair possible, if you want to be a real stair builder, you're going to have to make your own rail parts (yes! You'll have to learn wood-turning, too, so you can make your own balusters and newel posts — but that's another story.) This article will show you how we make volutes in our shop. We didn't invent anything here — the volute in this article could have been made by a Boston stair builder for a brownstone in Beacon hill in 1790, but we will show you a few modern tricks and techniques that make things go faster, particularly computer drafting, and power carving. If you have good carpentry skills, a shop space with basic woodworking tools, and an adventurous spirit, carving a volute might be a good place to jump your finish carpenter chops up to the next level.

The drawings

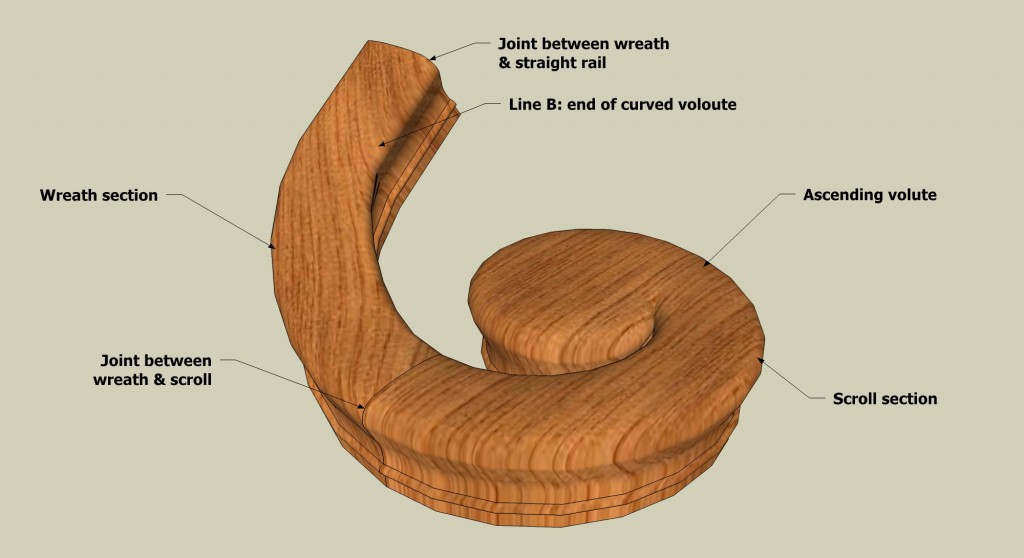

A volute is really made from two pieces: the scroll section, which is the portion of the volute that is level and spirals to an eye, and the wreath section.

A wreath is a stair building term for any compound curved piece of rail.

I draw the volute full size in both plan (from the top) and in elevation (from the side). Then I use these drawings to make full size patterns of both pieces. The patterns will go to the shop and be used to saw out the blanks and then carved. At the end of this story, Mike Kennedy will show you how that's done.

Before you start

Here's what you need to know before you start your drawing:

- What is the stair rise and run?

- What does the rail look like — it's best to have section or piece of the rail.

- What's the code on how wide and high the rail must be?

- How wide is the volute? And are you sure there's enough room?

Think about the design, too. You don't want a volute that ends at the center too big — like a dinner plate, or one that ends too small, like a cabinet knob.

Layout the volute

To draw the volute in plan view, I follow the same procedure every time. I draw the skirt board, second tread, baluster, and a short section of straight rail. Then I draw the volute. Next, I draw the bottom tread, because the stair is going to be better if the shape of the bottom tread follows the shape of the volute. Besides, I'll need a pattern for the tread and riser too, and the drawing provides that pattern.

Start with the second riser

Here are a few tips that should help you better understand the process of drawing a volute by hand. Watch the video, read these tips, do both again, and then practice drawing a volute yourself.

The first step in drawing the volute is establishing the edge of the skirt board and the edge of the second riser. Where they come together I draw a baluster. The centerline of the handrail goes through the center of the baluster, and the inside and outside of the rail are drawn 1-3/8" parallel to the centerline, to give a rail which is 2-3/4" wide. Once these elements are drawn, I measure downhill 2 in. from the second riser to draw the first stop line, where the straight rail meets the curved volute. I've found that 0 to 4 in. will work on most stairs: I want to design the stair so that the curve of the bullnose on the bottom tread follows the curve of the volute; that way all the balusters will have the same relation to the bottom tread as they have to the straight part of the stair. In other words, the face of all the balusters will be plumb flush with the face of the skirt and with the riser of the bullnose tread. If 2 in. doesn't work, it doesn't mean you have to start all over. You can just redraw the location of the riser until the bullnose tread looks right!

![v1[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/v1colored-1024x542.jpg)

I want to design the stair so that the curve of the bullnose on the bottom tread follows the curve of the volute…

The width of the volute also has to relate to the width of the rail; and it has to fit in the amount of available space — a narrow hallway wall can pose a real problem! Given enough space, most of the time, I've found that an 11in. volute works well with a 2 3/4 in. rail, and a 1 in. shrinkback.

The Shrinkback

![v2[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/v2colored2-1024x542.jpg)

A shrinkback is the amount that the spiral decreases every quarter turn of the volute. In this case, with a 11 in. volute and a 1 in. shrinkback, my first radius will be 6 in. (above), my second radius will be 5 in. (below), which adds up to the total width of the volute, 11 in.

![v3[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/v3colored1-1024x542.jpg)

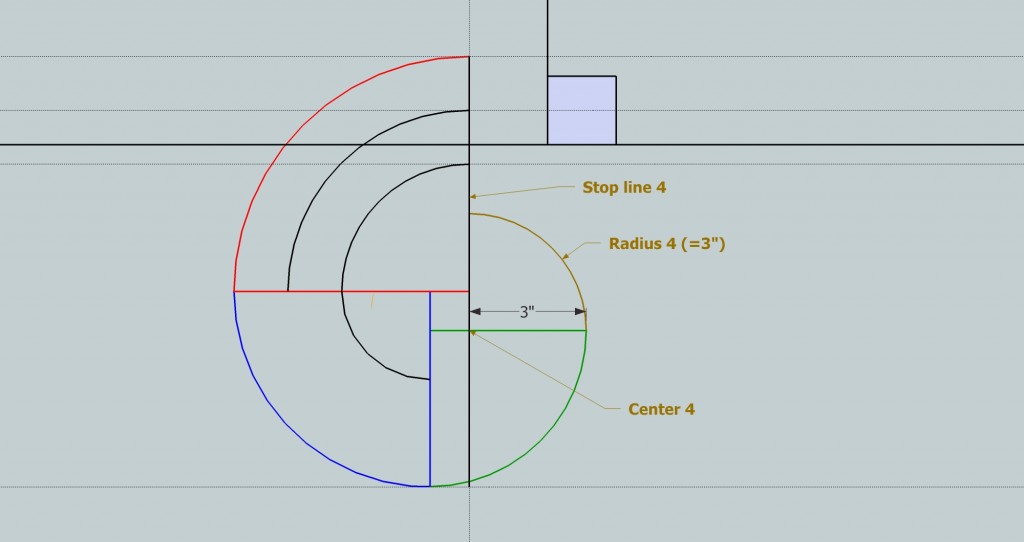

![v4[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/v4colored-1024x542.jpg)

For every quarter turn, I shrink 1 in. toward the interior of the volute, and each time I also draw a stop line at 90 degrees through the new center point — which establishes the end of each quarter turn.

I make this same step for radiuses #1, #2, #3, and #4.

The forth radius center point is established automatically, it's the intersection of the spring line and the stop line from the #3 radius. At this point, the centers have formed a 1-in. square. Radius 4 starts at stop line 3, and ends up back on the original start line.

![v6[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/v6colored2-1024x542.jpg)

For the fifth radius, the shrink back is 1/2 in. instead of 1 in., otherwise the spiral won't close in on itself like a nautilus shell. A 1/2 in. shrink back makes the radius 2 1/2 in.

![v7[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/v7colored-e1300813361788.jpg)

For the sixth radius, the shrink back is also 1/2 in. instead of 1 in. And that completes the spiral. The center of the last radius is the center of the 1-in. square; it's the center of the eye of the volute; and it's the center of the volute newel.

The scroll section is the level part of the volute. The pattern for the scroll section can be taken directly off this plan view drawing and used to bandsaw a blank out of a piece of wood the thickness of the rail. Watch the video below to see Mike Kennedy layout the grain of the volute.

Layout the wreath

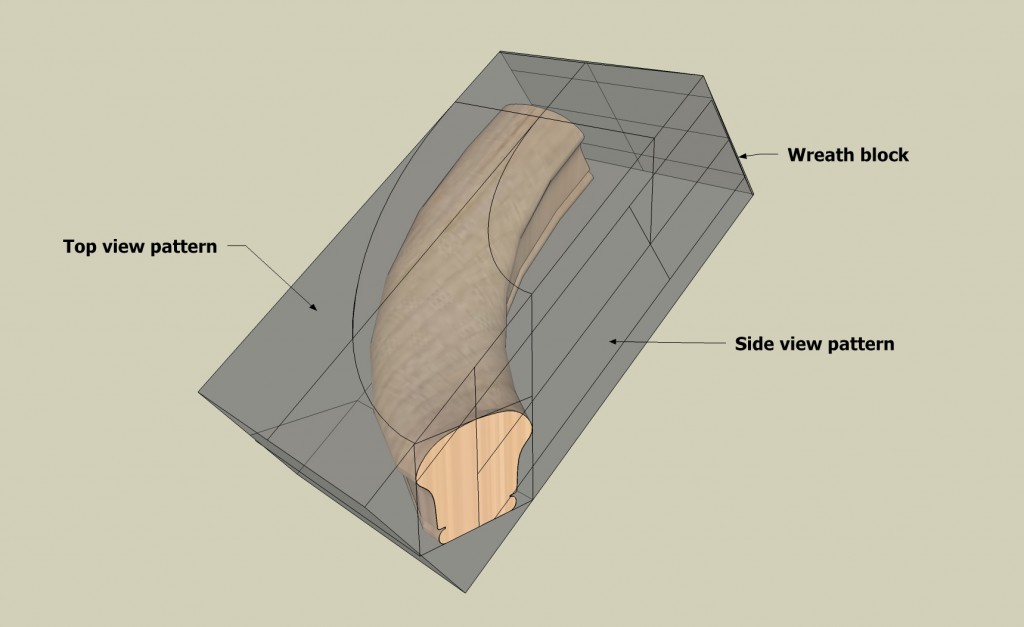

The wreath section is the upper section of the volute, which transitions from raked to level as it turns through the first 90 degrees. It has a compound curve because it curves in both plan and elevation. That compound curve makes it much more difficult to draw. In fact, it's even difficult to visualize. Look at the animation below and you'll see the drawing and the two patterns we're about to create.

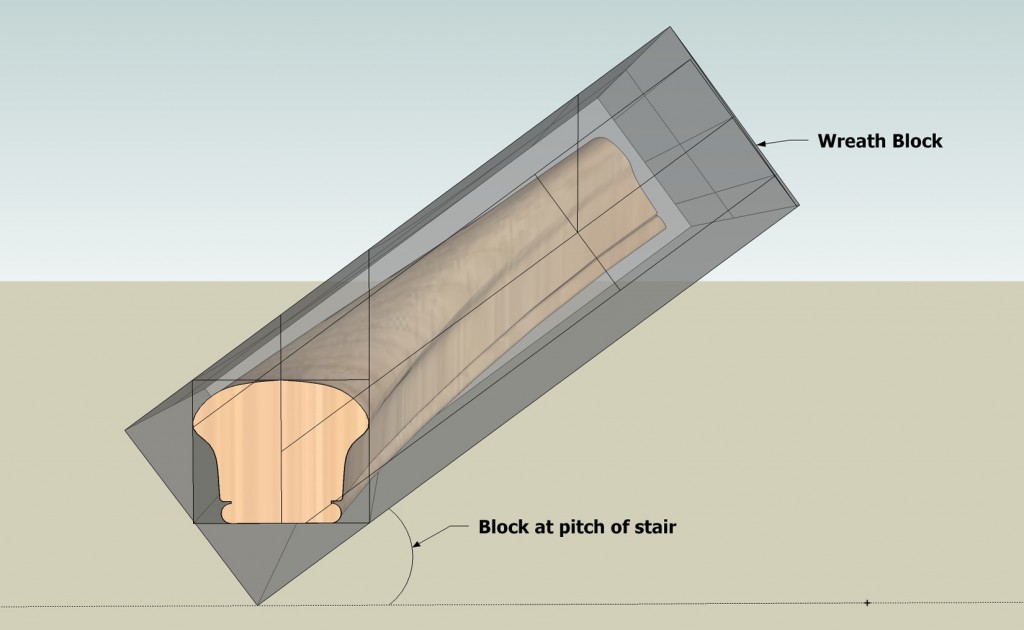

We have the plan view of the wreath from the volute drawing. In order to make a pattern for cutting the wreath from a block of wood, I first turn the scroll section drawing 90 degrees, so that I can see the elevation of the wreath. You'll see me turn the drawing in the video, but the Sketchup drawings included with the text start with the stair turned horizontally.

Because the wreath turns and twists, curving in plan and elevation, I need two drawings, both of which are drawn in elevation and plan view. I know this is going to confuse a lot of readers. When I first learned how to draw a wreath, the only guide I had was a drawing in a fifty year old book. Learning from that drawing felt like breaking my own leg over and over again. It took me the better part of a week to figure it out the first time.

I've been trying to explain this process to my friend Gary Katz for ten years; now he wishes he'd paid better attention in geometry class! Most of you will get it much quicker! I'm sure the video, this additional text, and the drawings (my thanks to Todd Murdock for the wonderful Sketchup illustrations!), will make it much easier to understand how to draw this complicated three-dimensional piece. Even Gary has drawn his own volute now, and we're going to make him carve it next time he visits the shop!

The Elevations

Because the wreath curves in plan and elevation, and because we want to get it out of the smallest piece of expensive and rare mahogany as possible, we have to visualize the block of wood at an angle. That angle is the pitch of the stair!

Also, because the wreath curves in two planes — it rises up the pitch of the stair and it turns 90 degrees with the spiral — we need to make a pattern for both the top and the side of the wreath.

Drawing the patterns

I always start with an elevation view of the entire volute, which will give us the pattern for the side of the block. I use a common shop class technique of drawing the elevation dimensions under the plan view, which makes it easy to carry the dimensions from the plan view to the elevation view.

The first line. Start by drawing a line down from the center of the handrail right where the scroll section and the wreath section join (Line A, below). I find that a 12-in or 13 in. line usually allows enough room to draw the whole elevation — the Side Pattern and the Top pattern; we'll do the side pattern first.

![pv-2.1[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-2.1colored3-1024x542.jpg)

The second line. Next, draw a horizontal line across the bottom of the drawing, like I said, about a foot below the plan view (bottom line, below, 13 in. below volute). That line helps establish the elevation of the handrail at the pitch of the stair. Think of that horizontal line as the run of the stair. Pretty soon, that line will become the centerline of the level scroll section.

![pv-1.5[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-1.5colored-1024x542.jpg)

![pv-1.75[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-1.75colored-1024x542.jpg)

Next, I draw the centerline of the raked handrail by connecting the rise and run lines at the rake of the stair (center diagonal line, below).

![pv-2[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-2colored2-1024x542.jpg)

After that, it's easy to draw the top and bottom of the raked handrail. The rail is 2 1/4 in. tall, so I place a line 1 1/8 in. above and 1 1/8 in. below the center line.

![pv-2.2[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-2.2colored-1024x542.jpg)

![pv-3[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-3colored-1024x542.jpg)

Next, I draw a line (K) square to the handrail so that it intersects line B at the centerline of the hand rail (see below). That's the exact location where the wreath meets the straight rail, and that square line would make a butt joint. However, the joint would be clipped slightly on the outer curve, and besides, I like to have a little extra wood on the wreath for carving the curve to the straight rail, so I add another 2 in. or 3 in. to the block; that is line L which becomes the glue line and the end of the block.

![pv-4[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-4colored-1024x542.jpg)

The Bottom Joint.Now we need to draw the joint where the bottom of the wreath meets the level handrail of the volute. To describe that joint, I have to establish both the height and the width of the handrail. I start by using the first horizontal line I drew, at the bottom of the drawing — that is the centerline of the level scroll section (below).

![pv-5[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-5colored2-1024x542.jpg)

Next, draw a line 1 1/8 above and below that centerline, establishing the side of the handrail in elevation (below).

![pv-5.5[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-5.5colored-1024x542.jpg)

![pv-6[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-6colored-1024x542.jpg)

Now I can trace a small piece of the handrail, in elevation, right on to the drawing, in the rectangle formed between F & G and the top and bottom of the horizontal rail. Believe it or not, that endgrain section is the face of the buttjoint at the bottom of the wreath!

![pv-6.5[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-6.5colored1-1024x542.jpg)

The side pattern. We've finished the elevation, now we can use it to make a paper pattern for the side of the block. We need a piece of wood thicker than the height of the 2 1/4 in. rail, so I use a piece of 12/4 or 2 3/4 in. thick stock.

To establish the top and bottom of the 2 3/4 in. block of wood on the elevation, draw a line 1 3/8 in. above and below the centerline of the raked rail (Lines D & E). To locate the lower end of the block, draw a line (J) square to D & E, so that it just misses the bottom corner of the handrail near the bottom of line F. Because the top of the block is already defined by line L (see Side-Top Views), we now have the side pattern complete (below).![pv-7[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-7colored-1024x542.jpg)

The top pattern. Before starting the Top Pattern, extend lines G & B to line D (below). By looking at the plan view of the volute above, we can tell that the wreath section is 6 in. wide. The block is already at the pitch of the stair, so it's easy to draw the top view at the same pitch, right above the side view.

![pv-8[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-8colored-1024x542.jpg)

I start by measuring 6 in. up from Line D, and strike Line H, parallel to line D (below). That establishes the width of the block and the top pattern. Extending lines J & L to line H completes the rectangle of the Top Pattern.

![pv-9[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-9colored-1024x542.jpg)

Next, draw a line 2 3/4 in. from and parallel to line H — that represents the inner edge of the straight rail (M, below).

![pv-10[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-10colored-1024x542.jpg)

Layout the Ellipses. Where line B intersects line D is the center point of both ellipses (P-1, below). Draw a line (B-1) square across the top of the pattern, parallel to line L-1. Line B-1 defines the ends of both the inner and the outer edge of the ellipse.

Don't forget we added a couple inches to the wreath to make it easier for Mike to blend the wreath and the straight rail. So from line B-1 to line L-1, the wreath is carved straight.

The intersection of line F and line D (P-2) is the starting point of the outer ellipse.

The intersection of line G and line D (P-3) is the starting point of the inner ellipse.

The intersection of line H and line B-1 is P-4.

The intersection of line M and line B-1 is P-5.

![pv-11[colored]](http://www.thisiscarpentry.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/pv-11colored-1024x542.jpg)

Draw the ellipses.

I use a trammel with two points and a pencil, and a small square, to draw the ellipses for the inside and outside of the rail. You'll have to watch the video to see how it's done, but here's how to set the trammels — just remember, always set one of the trammel points on P-1!

For the outside ellipse, put the pencil on P-4, then set the inner trammel point on P-1. Next, move the pencil to P-2, then set the outer trammel point on P-1. Swing the ellipse with the points held against the square the way I do it in the video.

For the inside ellipse set the pencil on P-5, then set the inner trammel point on P-1. Next, move the pencil to P-3 and set the outer trammel point on P-1. Again, swing the ellipse with the points held against the square the way I do it in the video.

Once the drawing and patterns are completed, I hand them off to Mike Kennedy. From that point on, the woodwork is in Mike's hands. Watch the video to see how Mike uses the paper patterns to cut the wreath out on the bandsaw.

And don't miss Mike's article on carving the volute. If you were lost at any point during this article, don't feel bad. I'm confident that if you watch the videos, read the text, look at the pictures, and draw it yourself, you'll understand the process and be a better carpenter for it.

If you use CAD software for drawing your work, here's a short video that should help.

If you read this story, then draw and carve a volute…please take pictures and send them in to the magazine! Share your work so we'll all learn more about our craft.

Source: https://www.thisiscarpentry.com/2009/07/15/drawing-a-volute/

0 Response to "How to Draw a Volute in Autocad"

Postar um comentário